Subject: Ascension

Dedication: In memory of Edward C. McGuire, D.D.

Maker/Date: German, 1885

Description

The Ascension took place 40 days after the Resurrection when Jesus led the disciples to Bethany. He raised his hands, blessed them and he was lifted up until a cloud took him out of their sight. This is shown in the window.

The Ascension story is told in Luke 24:50-53, Acts 1:3-11.

The Acts of the Apostles states that the disciples were in Jerusalem. Jesus appeared before them and commanded them not to depart from Jerusalem, but to wait for the”Promise of the Father”. He stated, “You shall be baptized with the Holy Spirit not many days from now” (Acts 1:5).

After Jesus gave these instructions, He led the disciples to the Mount of Olives. Here, He commissioned them to be His witnesses “in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). It is also at this time that the disciples were directed by Christ to “go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19). Jesus also told them that He would be with them always, “even to the end of the world” (Matthew 28:20).

Luke 24:50-51 “When he had led them out to the vicinity of Bethany, he lifted up his hands and blessed them. While he was blessing them, he left them and was taken up into heaven”

Acts 1:9 “After he said this, he was taken up before their very eyes, and a cloud hid him from their sight.”

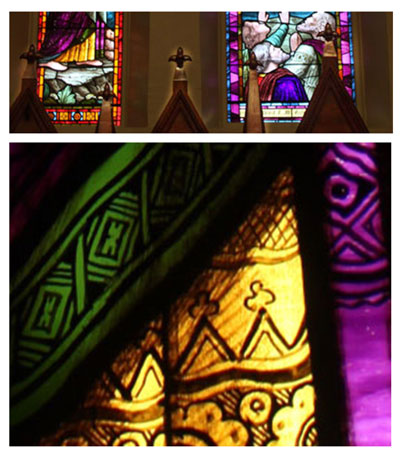

As the disciples were gazing upwards, two angels appeared with them dressed in white. This is not depicted here in this window. Instead, he is shown, arms raised, disappearing into a cloud with his feet and the hem of his clothes visible. His feet and hand still show scars of the crucifixion.

The window is in the form of a triptych or three panels. The left Apostle is Peter.

In the Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives, there is an indentation of a rock that is meant to be Jesus’ last footprint on the earth. The rock is partially shown on the left window which depicts St. Peter. Jesus asked the disciples, ‘But who do you say that I am?’ and Peter replied ‘You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.’ As a result of that declaration, Jesus said in v 19, ‘I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven…’The keys are shown in the middle of the picture.

The right image is probably that of John, the beloved who was always with him. John is always depicted as a young, smooth-faced disciple.

The other 8 disciples are present – three in the bottom right of St. Peter, three in the middle, two in the John window. Judas was not there since he had hanged himself and neither was Thomas.

The Peter and John sections of the triptych have flower details toward the bottom of each image:

Lilies of the Valley are considered a sign of Christ’s second coming. Acts 1:11 speaks of the second coming – “‘Men of Galilee,’ they said, ‘why do you stand here looking into the sky? This same Jesus, who has been taken from you into heaven, will come back in the same way you have seen him go into heaven.'” The lilies are the promise of a better world. It is said that Lilies of the Valley grew from the spot where Mary’s tears hit the ground at the foot of the cross.

One other detail is possibly the reredos shown in Peter’s gown. If so this would date the reredos before 1885. Here is the reredos in front of the Ascension window and below that the detail in Peter’s gown.

We know the church was under transformation in the 1870s. The protestant character of the Protestant Episcopal Church was emphasized more than the Episcopal for much of the 19th century. Until the 1870s, Bishop Meade kept the Episcopal Church thoroughly in the protestant camp. However, in the 1830’s the Oxford Movement grew up in England and over the next 50 years spread to America which emphasize Catholic influences. It would be a re-emphasis of both Catholic teachings and rituals. The 1870s witnessed physical changes in the church accompanying this shift. The appearance of the catholic-influenced reredos and the removal of the high pulpit which had dominated St. George’s was part of the change which may be depicted in the window. The decision to install a stained glass window, part of the Catholic heritage, also illustrated the influence of the Oxford Movement.

This window was dedicated to Rev. Edward McGuire, who served St. George’s 45 years. By the time this window was dedicated in 1885, 27 years after McGuire’s death in 1858, the last of his generation would have been active in St. George’s. The window is both a memorial to McGuire and to those who helped build up the 3rd church from 1849. Here is the dedication at the bottom of the Jesus section.

Another detail of the window is the lighting outside so that the window can be illuminated at night. It took 60 years off and on to get it done but was completed in 2007. The story is here.

The European Background of the Window

Germany has some of the oldest stained glass windows. The window was done before there was a definitive American school of stained windows

The oldest complete European windows are thought to be five relatively sophisticated figures in Augsburg Cathedral. Notable Romanesque windows with more complicated religious motifs are in Cologne and Strasbourg Cathedrals and the Franciscan Monastery of Konigsfelden.

Stained Glass windows fell out of favor from the late medieval age until the 19th century. The reasons were religious, political and aesthetic. The Church had been the principal patron of the arts. The new Protestants were hostile to elaborate art and decoration.

By 1640 colored glass was very scarce. This necessitated painting on white glass with enamels. The little decorative glass that was produced was mostly small heraldic panels for city halls and private homes. Stained glass that had been so popular just a few years before was no longer in demand

It was revived in Germany and Austria in the 19th century. In 1809, a group of young artists in Vienna defied their academic teachers and founded an art cooperative they called “The Brotherhood of Saint Luke.” Within a year, they were living in a commune in an abandoned monastery in Rome. They thought of themselves as following Albrecht Durer, who had traveled to Rome to study, and as being influenced by Raphael and Perugino. They were called The Nazarenes, first in mockery, but later with grudging admiration. The art of the Nazarenes was readily adaptable to stained glass because they used flat colors and bold outlines. They influenced stained glass even though they did not work in the medium.

Further German influences include Michael Sigismund Frank, who did his first glass painting in 1804, became the first manager of the Royal Bavarian Glass Painting Studio in 1827, and Max Ainmiller of Munich supplied some windows for Peterhouse in Cambridge University in 1855. Many consider Ainmiller’s most important work to be windows for the Cologne Cathedral in 1848.

Franz Mayer founded a studio in Munich, which at first, produced sculpture and marble altars. In 1860, the studio began making stained glass. The studio restored medieval windows and executed new windows all over the world, including many to the US. They are famous for heroic sized picture windows, extremely representational, with all the saints unmistakably German, that is, fair-skinned, robust and hearty figures.

The Oidtmann studios for glass and mosaics were founded in 1857 by a medical doctor and student of chemistry, Dr. H. Oidtmann. Working with glass slides inspired him to study stained glass. He founded a small studio as a sideline, but it soon grew into a major enterprise with 100 employees. At his death, his son Heinrich II, also a medical doctor and stained glass scholar, took over the stained glass studio. He wrote the book: Rhenish Stained Glass from the 12th to the 16th Centuries. He, too, died in his 50s, leaving the completion of his second volume to his son, Heinrich Oidtmann III. When Heinrich III died at the age of 40, his wife continued the studio.