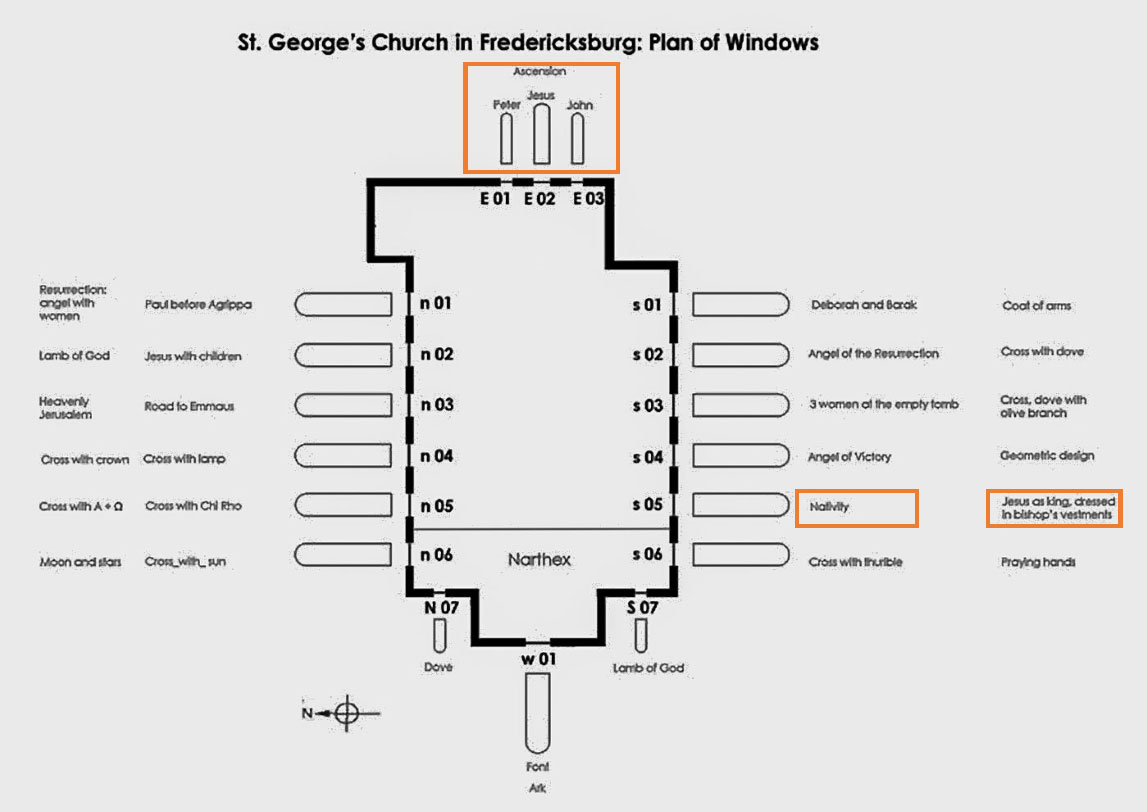

1. Ascension, 1885

Subject: Ascension

Dedication: In memory of Edward C. McGuire, D.D.

Maker/Date: German, 1885

Description

The Ascension took place 40 days after the Resurrection when Jesus led the disciples to Bethany. He raised his hands, blessed them and then was lifted up until a cloud took him out of their sight. This is shown in the window.

The Ascension story is told in Luke 24:50-53, Acts 1:3-11.

The Acts of the Apostles states that the disciples were in Jerusalem. Jesus appeared before them and commanded them not to depart from Jerusalem, but to wait for the”Promise of the Father”. He stated, “You shall be baptized with the Holy Spirit not many days from now” (Acts 1:5).

After Jesus gave these instructions, He led the disciples to the Mount of Olives. Here, He commissioned them to be His witnesses “in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). It is also at this time that the disciples were directed by Christ to “go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19). Jesus also told them that He would be with them always, “even to the end of the world” (Matthew 28:20).

Luke 24:50-51 “When he had led them out to the vicinity of Bethany, he lifted up his hands and blessed them. While he was blessing them, he left them and was taken up into heaven”

Acts 1: 9 “After he said this, he was taken up before their very eyes, and a cloud hid him from their sight.”

As the disciples were gazing upwards, two angels appeared with them dressed in white. This is not depicted here in this window. Instead, he is shown, arms raised, disappearing into a cloud with his feet and the hem of his clothes visible. His feet and hand still show scars of the crucifixion.

The window is in the form of a triptych or three panels. The left Apostle is Peter.

In the Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives, there is an indentation of a rock that is meant to be Jesus’ last footprint on the earth. The rock is partially shown on the left window which depicts St. Peter. Jesus asked the disciples, ‘But who do you say that I am?’ and Peter replied ‘You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.’ As a result of that declaration, Jesus said in v 19, ‘I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven…’The keys are shown in the middle of the picture.

The right image is probably that of John, the beloved who was always with him. John is always depicted as a young, smooth-faced disciple.

The other 8 disciples are present – three in the bottom right of St. Peter, three in the middle, two in the John window. Judas was not there since he had hanged himself and neither was Thomas.

The Peter and John sections of the triptych have flower details toward the bottom of each image:

Lilies of the Valley are considered a sign of Christ’s second coming. Acts 1:11 speaks of the second coming – “‘Men of Galilee,’ they said, ‘why do you stand here looking into the sky? This same Jesus, who has been taken from you into heaven, will come back in the same way you have seen him go into heaven.'” The lilies are the promise of a better world. It is said that Lilies of the Valley grew from the spot where Mary’s tears hit the ground at the foot of the cross.

One other detail is possibly the reredos shown in Peter’s gown. If so this would date the reredos before 1885. Here is the reredos in front of the Ascension window and below that the detail in Peter’s gown.

We know the church was under transformation in the 1870s. The protestant character of the Protestant Episcopal Church was emphasized more than the Episcopal for much of the 19th century. Until the 1870s, Bishop Meade kept the Episcopal Church thoroughly in the protestant camp. However, in the 1830s the Oxford Movement grew up in England and over the next 50 years spread to America which emphasize Catholic influences. It would be a re-emphasis of both Catholic teachings and rituals. The 1870s witnessed physical changes in the church accompanying this shift. The appearance of the catholic-influenced reredos and the removal of the high pulpit which had dominated St. George’s was part of the change which may be depicted in the window. The decision to install a stained glass window, part of the Catholic heritage, also illustrated the influence of the Oxford Movement.

This window was dedicated to Rev. Edward McGuire, who served St. George’s 45 years. By the time this window was dedicated in 1885, 27 years after McGuire’s death in 1858, the last of his generation would have been active in St. George’s. The window is both a memorial to McGuire and to those who helped build up the 3rd church from 1849. Here is the dedication at the bottom of the Jesus section.

Another detail of the window is the lighting outside so that the window can be illuminated at night. It took 60 years off and on to get it done but was completed in 2007. The story is here. In 2018, the church is looking to change the lighting to LED’s.

The European Background of the Window

Germany has some of the oldest stained glass windows. The window was done before there was a definitive American school of stained windows

The oldest complete European windows are thought to be five relatively sophisticated figures in Augsburg Cathedral. Notable Romanesque windows with more complicated religious motifs are in Cologne and Strasbourg Cathedrals and the Franciscan Monastery of Konigsfelden.

Stained Glass windows fell out of favor from the late medieval age until the 19th century. The reasons were religious, political and aesthetic. The Church had been the principal patron of the arts. The new Protestants were hostile to elaborate art and decoration.

By 1640 colored glass was very scarce. This necessitated painting on white glass with enamels. The little decorative glass that was produced was mostly small heraldic panels for city halls and private homes. Stained glass that had been so popular just a few years before was no longer in demand

It was revived in Germany and Austria in the 19th century. In 1809, a group of young artists in Vienna defied their academic teachers and founded an art cooperative they called “The Brotherhood of Saint Luke.” Within a year, they were living in a commune in an abandoned monastery in Rome. They thought of themselves as following Albrecht Durer, who had traveled to Rome to study, and as being influenced by Raphael and Perugino. They were called The Nazarenes, first in mockery, but later with grudging admiration. The art of the Nazarenes was readily adaptable to stained glass because they used flat colors and bold outlines. They influenced stained glass even though they did not work in the medium.

Further German influences include Michael Sigismund Frank, who did his first glass painting in 1804, became the first manager of the Royal Bavarian Glass Painting Studio in 1827 and Max Ainmiller of Munich supplied some windows for Peterhouse in Cambridge University in 1855. Many consider Ainmiller’s most important work to be windows for the Cologne Cathedral in 1848.

Franz Mayer founded a studio in Munich, which at first, produced sculpture and marble altars. In 1860, the studio began making stained glass. The studio restored medieval windows and executed new windows all over the world, including many to the US. They are famous for heroic sized picture windows, extremely representational, with all the saints unmistakably German, that is, fair-skinned, robust and hearty figures.

The Oidtmann studios for glass and mosaics were founded in 1857 by a medical doctor and student of chemistry, Dr. H. Oidtmann. Working with glass slides inspired him to study stained glass. He founded a small studio as a sideline, but it soon grew into a major enterprise with 100 employees. At his death, his son Heinrich II, also a medical doctor and stained glass scholar, took over the stained glass studio. He wrote the book: Rhenish Stained Glass from the 12th to the 16th Centuries. He, too, died in his 50s, leaving the completion of his second volume to his son, Heinrich Oidtmann III. When Heinrich III died at the age of 40, his wife continued the studio.

2. Nativity, 1943

Lower Subject: Nativity

Inscription: none

Dedication: In memory of Sue Young Lallande and John James Lallande, Louise Lallande Hoyt and Lindley Murray Ferris

Maker/Date: Wilbur Herbert Burnham, Boston, Massachusetts, 1943

Background – This was the last window added to St. George’s a quarter of a century after the last window, a Tiffany, in 1917. It was a donation from outside the Parish though the family had a direct descendant at St. George’s, John J. Young (1814-1901). Stained glass styles had changed significantly since the last window.

This window would have been typically found in a neo-gothic church, not in a church like St. George’s with Romanesque architecture.

Gothic Revival first appeared in the mid-19th century with architects such as Richard Upjohn, responsible for Trinity Church, Wall Street, NY of 1846. In Europe and the United States, this style of architecture was seen as a return to stability after a period of dishevel in the Revolutions of 1848 and earlier. The architecture featured pointed arches, a definite vertical emphasis with thinner lines.

In the 20th century, influenced by architects such as Ralph Adams Cram, the United States experienced a second Gothic Revival. Cram was the architect of Princeton University and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York.

Cram emphasized the “purity of materials” and a return to basic principles of constructing churches. This was in keeping with the proponents of the original Arts and Crafts movement, but Cram narrowed it down to the 13th-century French Gothic window as the primary source of inspiration.

What was the Arts and Crafts Movement? Arts and Crafts designers sought to improve standards of decorative design. It stood for traditional craftsmanship using simple forms, going back to original methods and often used medieval, romantic, or folk styles of decoration. It was a reaction against a perceived decline in standards that the reformers associated with machinery and factory production.

The movement began in England and particularly William Morris (1834-1896). The ideas of its proponents were disseminated in America through journal and newspaper writing, as well as through societies that sponsored lectures and programs. Boston, historically linked to English culture, was the first city to feature a Society of Arts and Crafts, founded in June 1897. This is important to note since the designer of the Nativity window was a major craftsman in Boston and was influenced by the movement. The movement had its heyday between 1890 and 1920.

Paralleling the Gothic revival in architecture was a revival in the stained glass industry of the use of designs and technology used by medieval window-makers. This medieval revival in stained glass, like the 19th-century Gothic revival in architecture, stressed the use of high-quality materials and careful work. Many of the glassmakers of the time went to Europe to study, learn from, and, eventually, in part imitate medieval glass making techniques. There were a number of published books by restorers with lavish reproductions and tracings or other detailed restoration drawings. N. J. H. Westlake’s History of Design in Stained Glass, 1891–1894 was one example.

They imitated the forms, medallion windows for the aisles and large figures for the clerestories. Many of the windows themselves are long, narrow, and terminate at the top in a pointed Gothic arch, a shape known as a lancet.

Makers imitated the color palette of Chartres, principally red and blue, with touches of secondary colors. All the color was in the glass and moved away from Tiffany’s use of painting. Colored glass, known as “metal” was made by adding various metallic oxides to the crucibles in which the glass was melted. Cobalt gave blue, copper green, iron red, gold cranberry, silver yellows and gold, copper makes greens and brick red. Since the ideal in the church was a “dim religious light” they imitated the patina of the ages with thin washes of glass paint and picked out highlights.

Wilbur H. Burnham, Sr., the creator of the Nativity window, was born in 1887 and founded his studio in Boston in 1922 toward the end of the Arts and Crafts Movement. He secured his first commission from Ralph Adams Cram. He began his work in Stained Glass while still a student at the Massachusetts School of Art. He advanced to the very front rank of his profession and was elected president of the Stained Glass Association of America for 1939, 1940, and 1941. Burnham died in 1974. His son carried on his work until he had to sell the studio in 1982. The records were given to the Smithsonian Institution.

Burnham was commissioned to design windows for churches and cathedrals in the United States and in Europe. Among his most notable works are windows in the Cathedral of Sts. Peter and Paul, Washington DC, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and Riverside Church in New York City, Princeton University Chapel, and the American Church in Paris. When the Nativity window was approved in 1939 and installed in 1943, Burnham was among foremost neo-gothic stained glass craftsmen and at the height of productive years.

The style of the window is very different than Tiffany – no opalescent glass and less enamel painting. Cram said Tiffany’s style was inappropriate for churches and not very religious.

The most prominent spokesman for the Gothic Revival in windows was Charles Connick. He lectured widely and wrote, the most respected and eloquent publication on the art form in the twentieth century. Connick expressed the opinion that stained glass’s first job was to serve the architectural effect; this opinion was in sharp contrast to the painterly effect that had dominated during the Tiffany era.

Burnham in the Church Monthly talking about his clerestory apse windows in Riverside Church, said “the first purpose was to give glory to God through a material which is the crowning accent to architecture.”

He went on to say that “stained glass appeals directly to the emotions. Being more closely allied to music than to painting, it thrills and overpowers and leaves us with a sense of richness and beauty simulating the orchestration of a great symphony.”

In a 1935 article in the journal Stained Glass, Burnham expressed his views about the importance of the medieval tradition in the harmony of the primary colors, red, blue, and yellow, with the complementary orange, green, and violet typical of his windows. His studies of medieval windows demonstrated that reds and blues should predominate and be in good balance – he believed “blues” had been overstressed.

Burnham also noted that windows should maintain high luminosity under all light conditions with the depth of color and amount of pigment useful in controlling glare invariably intense light. Burnham agreed with the concept of unity in multiple windows, which are most easily created when there has been an early, consistent policy by church leaders in collaboration with the designer.

Description –

Burnham’s windows are divided into different iconographical “fields.” The window works from top to bottom with the standing characters to the top and those sitting around Jesus to the bottom.

The center of the window contains the main story and is the largest and most visible part of the window which is the baby Jesus. Along with Jesus, the star divides the scene with a touch of the rose for new life just above Jesus. Mary Joseph and King’s heads bend toward Jesus creating another emphasis for the child. The yellow color extends from the star down to the hay surrounding Jesus, which illuminates him.

Mary and Joseph on the right are clearly separated from the visitors on the left. The former have halos. All the figures turn inward toward the main storyline, the birth of Christ.

Mary’s head is not centered within the window, but bends to one side, thus making the three figures stand out from the otherwise symmetrical composition.

The figures are European and could have been taken from Renaissance or earlier European paintings. It is very iconic, inclusive and balanced – the two shepherds, one King, and the angel strumming a lute on the left against the other characters. The colors are both vivid and varied.

Two lambs in the foreground, with their wool depicted in a stylized pattern, add to the richness of the overall design. Placing the lambs close to the Infant Jesus symbolizes Christ as the Lamb of God.

The brilliant reds, yellows, greens, and blues of this window (as with all of Burnham’s windows) stand out with tremendous clarity and brightness, with the primary colors dominant and with the secondary colors used sparingly. The blue sky provides a backup against the red wings of the angel, the cow, and the different color of the halos.

Burnham often used color opposites to add brilliance to the scene and to pull the viewer’s eyes toward the image of Mary. The intense yellow/gold halo surrounded by the light blue head covering is also very eyecatching. Burnham often uses complementary colors (opposites on the color wheel) often red vs. green, or blue and orange.

The clothes are multi-colored – red, blues and different shades of green. They are symbolic. Red, the color of divine love and devotion from, the angel, is balanced by a deep blue (color of Mary symbolizing spiritual truth and divine wisdom). The design is completed by sparkling accents of white for faith and purity, gold for spiritual victory, and green for youth and immortality.

This is a bright window, especially in the full sunlight that reinforces the event. The use of small pieces of multicolored glass creates the effect. This contrasts with the Church’s Tiffany window where the figures could be undistinguished from a painting. The characters are definitely those of windows without the preciseness of the Tiffany approach with the use of staining different pieces of glass.

Burnham’s must have thought of the interplay of the sun coming through the window. The morning sun shining through the window comes right through the star projecting star rays on the upper gallery.

The medieval details at the top and bottom surround the nativity and create the appearance of a medieval city. The sides are curved creating a stage for the presentation of the Nativity window itself. The borders on the left and right sides provide a feeling of lightness. This effect is in part created by the borders having a predominance of white glass and architectural figures pointed up.

The details in the bottom portion are very medieval. On the left and right side are the two St. George Crosses. It is a red cross on a white background The cross has its origins in the 12th century. It was used by a variety of Italian city-states – Bologna, Padua, and Genoa. The flag became associated with crusaders.

The red cross was introduced to England by the late 13th century, but not as a flag, and not at the time associated with Saint George. It was worn by English soldiers as identification from the early years of the reign of Edward I (1270’s). After the Reformation, it became associated with England as a whole.

The window decorations on the top and bottom appear to be associated with a cathedral and lead to a pointed Gothic arch with a lancet. The top section above the star may be a triforium, a gallery or arcade above the arches of the nave, choir, and transepts of a church. Inside are more lancets. There are pinnacles on either side of the star, a sharp point ornament capping the piers or flying buttresses. There is also a tympanum, a semi-circular or triangular decorative wall surface over an entrance, door or window, which is bounded by a lintel and arch. It often contains sculptures or other imagery or ornaments.

3. Christ the King, 1943

Upper Subject: Christ the King. We celebrate Christ the King as the last Sunday in Pentecost, the week before Advent begins.

Inscription: none

Dedication: In memory of Sue Young Lallande and John James Lallande, Louise Lallande Hoyt and Lindley Murray Ferris

Maker/Date: Wilbur Herbert Burnham, Boston, Massachusetts, 1943

Background –

Background of the maker, Willard Burnham is here

We celebrate Christ the King Sunday as the last Sunday of Ordinary Time just before we begin Advent. It is the switch in the Liturgy between Years A, B, and C.

The earliest Christians identified Jesus with the predicted Messiah of the Jews. The Jewish word “messiah,” and the Greek word “Christ,” both mean “anointed one,” and came to refer to the expected king who would deliver Israel from the hands of the Romans. Christians believe that Jesus is this expected Messiah. Unlike the messiah most Jews expected, Jesus came to free all people, Jew and Gentile, and he did not come to free them from the Romans, but from sin and death. Thus the king of the Jews, and of the cosmos, does not rule over a kingdom of this world.

Christians have long celebrated Jesus as Christ, and his reign as King is celebrated to some degree in Advent (when Christians wait for his second coming in glory), Christmas (when “born this day is the King of the Jews”), Holy Week (when Christ is the Crucified King), Easter (when Jesus is resurrected in power and glory), and the Ascension (when Jesus returns to the glory he had with the Father before the world was created).

The four Gospel writers of the Bible’s Christian Testament all refer to Christ, after His Resurrection, variously as “King of Kings“; ”King of Glory“; “All-Powerful”; “All Ruler”; “Lord of Lords” and similar lofty, Imperial-style titles. Obviously, this was against the backdrop of the presence of the Holy Land’s rulers at the time, the Roman Emperors.

The celebration of Christ the King in modern times came from the Catholics in the 20th century. Pope Pius XI wanted to specifically commemorate Christ as king and instituted the feast in the Western calendar in 1925. Pius connected the denial of Christ as king to the rise of secularism. Secularism was on the rise, and many Christians, even Catholics, were doubting Christ’s authority, as well as the Church’s, and even doubting Christ’s existence. Pius XI, and the rest of the Christian world, witnessed the rise of dictatorships in Europe and saw Catholics being taken in by these earthly leaders

Pius hoped the institution of the feast would have various effects. They were:

- That nations would see that the Church has the right to freedom, and immunity from the state.

- That leaders and nations would see that they are bound to give respect to Christ.

- That the faithful would gain strength and courage from the celebration of the feast, as we are reminded that Christ must reign in our hearts, minds, wills, and bodies.

Description-

The upper subject projects the baby Jesus into Christ the King image, in Bishops’ vestments.

Jesus with crown outstretched arms is in the shape of the cross. Above Jesus INRI stems from the Latin phrase ‘Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum’ meaning ‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’.

He is flanked at the top with two seraphs and fleur-de-lis. The word “seraphs” means “burning ones” or nobles. They are also sometimes called the ‘ones of love’ because their name might come from the Hebrew root for ‘love’. They are only fully described in the Bible on one occasion. This is in the book of the prophet Isaiah when he is being commissioned by God to be a prophet and he has a vision of heaven. There are six wings shown but only two are used for flying.

Jesus is inset in an oval design. As with the lower window, the yellow color accentuates Jesus, now an adult. Red from the cherubs, the Celtic cross behind Jesus and his vestments grouped together are also in the shape of a cross and provide additional emphasis on Jesus. Jesus’ head is surrounded on the borders by medieval pointed arches.

The two symbols in the middle are Alpha and Omega from Revelation 21:- “I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end.” It comes in a passage dealing with the end of history. So Christ is the Alpha and Omega of all things.”

Below Alpha and Omega are two angels in medieval costume with the wings outreached. The color green for youth and immortality. Angels can be considered immortal. In Luke 20:35-36, it is written”..but those who are considered worthy of a place in that age and in the resurrection from the dead neither marry nor are given in marriage. Indeed they cannot die anymore, because they are like angels and are children of God, being children of the resurrection.”